There’s nothing more frustrating in a game of Dungeons and Dragons than a prolonged combat with uninteresting and flat action descriptions. “You hit,” “That’s a miss,” even descriptions in the vein of “Your sword swings wide, narrowly missing the enemy,” all feel unsatisfying, especially in unchanging repetitive doses. As DMs, we already have a lot of moving pieces to manage in our games, especially when running combat. Between tracking initiative, managing monster and NPC statistics, maneuvering physical or digital maps and tokens, moderating rules quibbles, our plates are full to overflowing. Is there a way we can improve the narrative quality of our combat without significantly adding to our mental load? I’m going to attempt to codify an approach that has helped me informally in my games, which once understood can be easily integrated into our combat management workflow.

In short, the approach is this:

If we reframe our understanding of Armor Class from a static threshold to a series of concentric defensive layers, we can inform our narrative based on which layer prevented an attack from succeeding.

We can find our starting point in perhaps the least surprising but most criminally underutilized sources of guidance in Fifth Edition Dungeons and Dragons: the venerated Dungeon Master’s Guide. In the Combat Options section in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, we are given an optional rule for hitting cover:

“When a ranged attack misses a target that has cover, you can use this optional rule to determine whether the cover was struck by the attack. First, determine whether the attack roll would have hit the protected target without the cover. If the attack roll falls within a range low enough to miss the target but high enough to strike the target if there had been no cover, the object used for cover is struck. If a creature is providing cover for the missed creature and the attack roll exceeds the AC of the covering creature, the covering creature is hit.”

Dungeon Master’s Guide p.272

In essence, if a ranged attack would have hit the target were it not for the AC boost received from the cover, then the cover is struck instead. It is a very logical guideline, and it certainly can help provide variety in our description options. However, the logic of this section need not be so limited in scope; why limit this perspective to ranged attacks and cover? Shouldn’t we want every aspect of our combat to be more dynamic and interesting?

While it was never a hard or firm rule, I have applied a version of this same logic to the combat in my games, beyond the circumstances of ranged attacks impeded by cover, to help encourage my creative narration abilities.

In order to broaden the application of this logic to our games, we must first understand the component parts at play.

The requisite conditions for this approach to be applicable are:

- a failed attack on a target in combat,

- a defensive threshold or bonus which sufficiently determines the failure of said attack (in the case of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, an interposing Cover condition), and

- an additional defensive sub-layer which would not have been sufficient to prevent the attack on its own (in the case of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, the target’s static AC).

The first condition is easily recognized when met, as combat is a staple function of Dungeons and Dragons Fifth Edition. The second, by the very nature of the game, comes hand in hand with the first, as part of the initial resolution of the mechanic. The third condition, the concept of defensive sublayers, is where we can truly dig into the meat of the matter.

What is Armor Class?

Defensive capabilities in D&D, as you almost certainly already know if you’re reading this, are aggregately represented by Armor Class:

“Your Armor Class (AC) represents how well your character avoids being wounded in battle. Things that contribute to your AC include the armor you wear, the shield you carry, and your Dexterity modifier. Not all characters wear armor or carry shields, however.”

Player’s Handbook p.14

In order to apply this logic beyond the DMG’s conditions of cover, we need to make sure we change the way we look at AC. It’s easy and far too common to view Armor Class in our mind’s eye as a static condition or threshold to be met, a number which is raised and lowered by equipment and effects but a number nonetheless. We must begin to view this value not as one static threshold, but rather a series of concentric thresholds. We then take them from being a series of numerical steps we use to determine our static Armor Class during character creation and then discard, to lasting narrative layers that continue to inform our game beyond their roles as components of the whole.

Natural Armor Class

Without armor or a shield, your character’s AC equals 10 + his or her Dexterity modifier.

Player’s Handbook p.14

The first layer of defense, a target’s natural evasiveness and difficulty to hit with an attack, comes from a creature’s Dexterity. Without any weapons, armor, or magical items, to bolster their hardiness, this is a creature’s pure ability to avoid being hit. To piggyback a line from the movie Dodgeball, these are the dodges, ducks, dips, dives, and dodges of the imaginative combat sphere. When an attack misses a target with a value that falls in this range (0 ↔ Natural AC), we know that the miss never made contact due to evasion, situational awareness, combat prowess, or the ineptitude of the attacker (see NOTE ON INEPTITUDE).

NOTE ON INEPTITUDE: We all like a little levity at the table; it’s what makes some natural ones as fondly memorable as other natural 20s. But when flavoring your narrations with ineptitude, use sparingly as it can quickly break table immersion. As with cooking, you can always add more of a strong spice, but you can’t take it out.

Protective Armor Class

The next defensive layer is perhaps the most obvious factor; armor. The namesake of the defensive statistic itself, this is the quintessential operative in making a creature difficult to hit. For the purposes of narrative effect, I am also including natural armors like Dragonborn and Draconic Soul Sorcerers’ scale defense, Tortles’ natural armor, and other natural forms of bolstering physical defense in this same layer (let’s call it Protective AC). While the first layer is comprised of abstracted components of physical capability, this is the first literal layer of protection on a creature.

When an attack misses a creature with a value that falls in this range (Natural AC ↔ Standard AC), we can immediately know that although the attack was aimed true and delivered with strength and skill enough to otherwise hit a creature, it is deflected, absorbed, or otherwise prevented by the physical layer of protection on a creature. Our action descriptions can now reflect that in-fiction truth; an arrow may sink into a beast’s thick hide, to no effect. A warhammer may ring with a resounding clang on an opponent’s breastplate, gauging a crater in the steel but leaving only a deep bruise where broken ribs should have been.

Interposing Armor Class

However, as illustrated by the there are other compounding factors that can raise Armor Class further. Aside from cover, there are also shields, spells, and other effects which create an additional interposing layer between a creature and its assailant. Let’s call this layer the Interposing AC. If an attack would have hit a creature with a value in this range (Protective AC ↔ Interposing AC), we know that the blow would have found its mark save for some interposing object or extraneous effect. The deft raising of a shield, just in time. An agile reflexive casting of a Shield spell. A bard’s flourishing blade, parrying the blow at the last moment.

These layers aren’t here for you to memorize; like I stated at the top of the article, we as DMs don’t need any more numbers and rules bouncing around our heads than we already do. But if you familiarize yourself with the concept behind the layers, you can approximate on the fly, allowing them to become a source of improvisational inspiration rather than a series of rules or statistics to dogmatically follow.

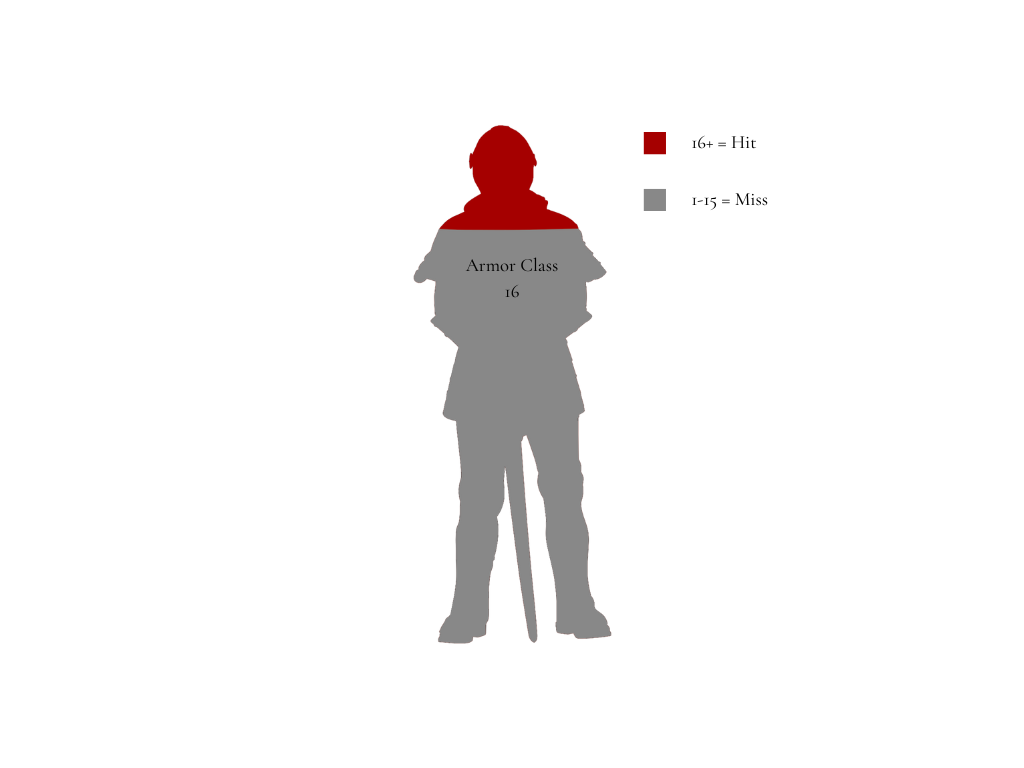

Now just in case I haven’t fully displayed how nerdy I can get about minutia, here is an illustrated diagram illustrating the principle in effect. Both figures represent a figure using the Guard statistics from the D&D 5e SRD; the left figure shows the traditionally static armor class with its binary options of hit and miss, while the right shows the same Guard with narratively interesting layers of Armor Class.

So what now?

Beyond using this principle with Armor Class, you can take the spirit behind the whole concept and apply it to more mechanics in your game! Any mechanic that has multiple potential thresholds to determine its success or failure can be given the same treatment. Rolls made with disadvantage that would have succeeded without the second die can be narrated as failing specifically due to the circumstance or ability that imposed the disadvantage, and the same can be ascribed to rolls that only succeeded because of advantage.

The rule of thumb we can take from this, even if you never sit down and calculate hard numerical values for your PCs’, NPCs’, and monsters’ AC Layers, is this:

If a roll’s success or failure is impacted by an intervening mechanical principle, allow your narration of the result to be based on the in-world catalyst for that mechanical effect.

I hope this helps you keep things as fresh and vibrant in your games as it has for me! Remember to treat them as suggestions and starting points, and they will give your busy GM’s brain one less obstacle to improvising an immersive tale for your players.